C. tetani usually enters a host through a wound to the skin and then it replicates. Once an infection is established, C. tetani produces two exotoxins, tetanolysin and tetanospasmin. Eleven strains of C. tetani have been identified, which differ primarily in flagellar antigens and in its ability to produce tetanospasmin. The genes that produce toxin are encoded on a plasmid which is present in all toxigenic strains, and all strains that are capable of producing toxin produce identical toxins.

Tetanolysin serves no known function to C. tetani, and the reason the bacteria produce it is not known with certainty. Tetanospasmin is a neurotoxin and causes the clinical manifestations of tetanus. Tetanus toxin is generated in living bacteria, and is released when the bacteria lyses, such as during spore germination or during vegetative growth. A minimal amount of spore germination and vegetative cell growth are required for toxin production.

On the basis of weight, tetanospasmin is one of the most potent toxins known. The estimated minimum human lethal dose is 2.5 nanograms per kilogram of body weight, or 175 nanograms in a 70 kg (154 lb) human. The only toxins more lethal to humans are botulinum toxin, produced by close relative Clostridium botulinum and the exotoxin produced by Corynebacterium diphtheriae, the causative agent of diphtheria.

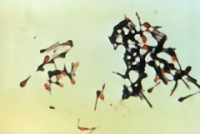

Tetanospasmin is a zinc-dependent metalloproteinase, that is similar in structure to botulinum toxin, but each toxin produces quite different effects. C. tetani synthesizes tetanospasmin as a single 150kDa polypeptide progenitor toxin, that is then cleaved by a protease into two fragments; fragment A (a 50kDa "light chain") and fragment B (a 100 kDa heavy chain) which remain connected via a disulfide bridge. Cleavage of the progenitor toxin into A and B fragments can also be induced artificially with trypsin.

Toxin Action

Tetanospasmin is distributed in the blood and lymphatic system of the host. The toxin acts at several sites within the central nervous system, including peripheral nerve terminals, the spinal cord, and brain, and within the sympathetic nervous system. The toxin is taken up into within the nerve axon and transported across synaptic junctions, until it reaches the central nervous system, where it is rapidly fixed to gangliosides at the presynaptic junctions of inhibitory motor nerve endings.

The clinical manifestations of tetanus are caused when tetanus toxin blocks inhibitory impulses, by interfering with the release of neurotransmitters, including glycine and gamma-aminobutyric acid. This leads to unopposed muscle contraction and spasm. Seizures may occur, and the autonomic nervous system may also be affected. Tetanospasmin appears to prevent the release of neurotransmitters by selectively cleaving a component of synaptic vesicles called synaptobrevin II.

It should be noted that the organism itself has no access to the nervous system, and yet tetanospasmin is directed toward the nervous system. The reason why this occurs, is still a subject of controversy. It's fairly known that toxins are by-products synthesized during bacterial growth, and their targets are determined by the presence or absence of specific receptors on human cells to which they can bind and exert their effect. This only explains why the tetanus toxin acts on the nervous system, but why it reaches a place to which the organism itself has no access may be an anomaly of nature.

From Wikipedia

Tidak ada komentar:

Posting Komentar